The biggest lie in fitness is that growth happens in the gym; in reality, it’s a precise biological repair process you’re likely sabotaging.

- The “anabolic window” is a 24-hour process, not a 30-minute sprint.

- Muscle recovery is dictated by hormonal cascades during deep sleep, not total sleep time.

- Cramps are a signal of sodium depletion, not just dehydration; water alone can be detrimental.

Recommendation: Shift your focus from training volume to optimizing your recovery cycles with targeted nutrition and sleep hygiene.

You train relentlessly, seven days a week. You hit every session with maximum intensity, chase personal records, and leave nothing in the tank. Yet, when you look in the mirror, the results are stagnant. You’re exhausted, perpetually sore, and frustrated. This is a common scenario for the dedicated gym enthusiast who believes more work automatically equals more growth. The prevailing advice is often simplistic: drink a protein shake immediately after your workout, get your eight hours of sleep, and just keep pushing.

This approach is fundamentally flawed because it ignores a critical biological truth: muscle tissue is not built during the act of lifting. The gym is where you create the stimulus—a controlled process of micro-trauma and metabolic stress. The actual growth, or hypertrophy, occurs during the hours and days that follow, through a complex and demanding series of biochemical repair cycles. Your lack of progress isn’t from a lack of effort, but a failure to facilitate this biological repair. You are creating a constant state of homeostatic disruption without allowing the systems to rebuild stronger.

But what if the key wasn’t adding another training day, but rather strategically engineering your recovery? This guide reframes the conversation from training volume to repair optimization. We will dissect the non-negotiable pillars of recovery from a biological standpoint. We will move beyond the myths and into the mechanisms, exploring how specific sleep stages trigger hormonal cascades, why electrolyte balance is more critical than water intake for cellular function, and how to interpret your body’s signals to build a truly effective, science-backed recovery protocol. This is not about training less; it’s about making the time you spend outside the gym count for more.

To navigate this complex biological landscape, this article breaks down the essential components of intelligent recovery. The following sections will guide you through the science of nutrient timing, sleep architecture, electrolyte management, and more, providing a clear roadmap to finally unlock the results your hard work deserves.

Summary: The Biology of Intelligent Muscle Repair

- Anabolic Window: Do You Really Need Protein Within 30 Minutes?

- Magnesium for Soreness: Which Form Actually Absorbs into Muscles?

- Deep Sleep vs. REM: Which Stage Repairs Physical Tissue?

- Sodium Depletion: Why Water Alone Won’t Stop Muscle Cramps?

- Foam Rolling: Does It Break Up Fascia or Just Cause Pain?

- Active Rest: Why Lying on the Couch Is Not the Best Recovery for Stress?

- How to Use Wearable Tech Data Without Becoming Obsessed with Numbers?

- Mobility for Longevity: Exercises to Prevent the “Shuffle” After 60?

Anabolic Window: Do You Really Need Protein Within 30 Minutes?

The concept of a 30-minute “anabolic window” is one of the most persistent and commercially exploited myths in fitness. The theory suggests that for maximal muscle growth, protein must be consumed immediately post-exercise. From a biological standpoint, this is an oversimplification that misunderstands the timeline of muscle protein synthesis (MPS). Resistance training triggers a prolonged increase in MPS, the process of building new muscle proteins. This isn’t a brief sprint; it’s a marathon. In fact, research demonstrates that muscle protein synthesis remains elevated by as much as 109% at 24 hours post-exercise, and can stay elevated for up to 72 hours, depending on training status and intensity.

The urgency is a fabrication. The body doesn’t operate with such a tight and unforgiving switch. The focus on this narrow window distracts from the most critical variable: total daily protein intake. A sufficient protein supply throughout the day ensures that amino acids are available when the cellular machinery for repair is active. Missing the 30-minute mark is inconsequential if your overall daily protein target is met and distributed reasonably across several meals.

Case Study: Protein Timing Irrelevance in Trained Men

A 2024 randomized controlled trial provided definitive evidence against the immediate post-workout protein dogma. The study, involving resistance-trained men on high-protein diets, found that the timing of protein intake relative to their workouts had no significant effect on gains in either muscle mass or strength. This confirms that for individuals consuming adequate daily protein, the obsession with a narrow anabolic window is not supported by science. The body is more resilient and adaptable than supplement marketing suggests; it prioritizes the total availability of resources over a specific, short-term ingestion schedule. This shifts the strategic focus from “when” to “how much” over a 24-hour cycle.

For the over-trained athlete, this means a fundamental shift in mindset. Instead of panicking about slamming a shake, focus on consistently hitting your daily protein goal (typically 1.6-2.2g per kg of body weight). Think of your nutrition as creating a 24-hour reservoir of amino acids, not a last-minute rescue mission. This approach reduces stress and aligns with the true biological timeline of muscle repair.

Magnesium for Soreness: Which Form Actually Absorbs into Muscles?

Magnesium is a critical cofactor in over 300 enzymatic reactions in the body, many of which are central to muscle function, energy production (ATP synthesis), and nervous system regulation. For athletes, its role in recovery is paramount, particularly for mitigating muscle soreness and promoting neurological downregulation after intense training. However, not all magnesium is created equal. The efficacy of a magnesium supplement is dictated almost entirely by its bioavailability—the percentage of the elemental mineral that can be absorbed and utilized by the body. Many common, inexpensive forms are poorly absorbed and offer little benefit beyond a laxative effect.

The form of magnesium determines its absorption pathway and its ultimate destination in the body. Magnesium oxide, a common form found in many low-quality supplements, has a bioavailability as low as 4%. This means 96% of the ingested mineral is passed through the digestive tract unabsorbed, often causing gastrointestinal distress. In contrast, chelated forms, where magnesium is bound to an amino acid, exhibit far superior absorption rates. For athletic recovery, selecting the right chelated form allows you to target specific biological outcomes, from improving sleep quality to enhancing cellular energy.

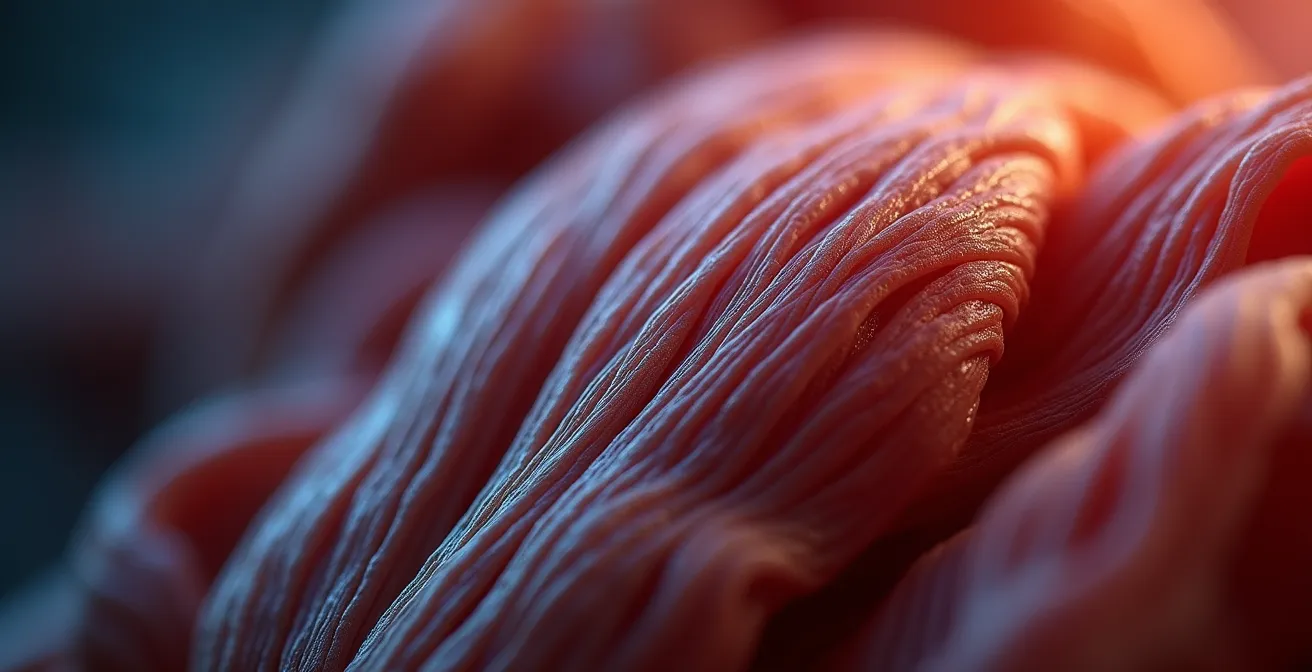

As this visualization metaphorically suggests, getting the mineral into the cell is the primary objective. For an athlete seeking to reduce soreness and improve sleep, Magnesium Glycinate is often the superior choice. Glycine is an inhibitory neurotransmitter, which works synergistically with magnesium to calm the nervous system, making it ideal for evening use to promote restorative sleep. For energy and pre/post-workout use, Magnesium Malate is a strong contender, as malic acid is a key component of the Krebs cycle, the body’s primary energy production pathway. Understanding these nuances is the difference between effective supplementation and wasting resources.

This table, based on an analysis of recovery nutrients, breaks down the key differences between common magnesium forms to guide intelligent selection for athletic recovery.

| Magnesium Form | Bioavailability | Primary Benefits | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Glycinate | High (80-90%) | Calming, sleep improvement | Evening recovery |

| Magnesium Malate | High (70-85%) | ATP production, energy | Pre/post workout |

| Magnesium L-Threonate | Moderate (crosses BBB) | Cognitive recovery | Mental fatigue |

| Magnesium Oxide | Low (4-10%) | Laxative effect | Not recommended |

Deep Sleep vs. REM: Which Stage Repairs Physical Tissue?

The common advice to “get 8 hours of sleep” is biologically imprecise. Total sleep duration is a poor metric for recovery if the quality and architecture of that sleep are compromised. Sleep is not a monolithic state; it is a dynamic cycle through different stages, each with a distinct neurochemical and physiological purpose. For an athlete, the most critical phase for physical repair is not REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep, which is primarily for cognitive and memory consolidation, but rather NREM Stage 3, also known as deep sleep or slow-wave sleep. This is the period of maximum somatic restoration.

During deep sleep, the body undergoes a profound hormonal shift. Brain activity slows, blood pressure drops, and blood flow is redirected from the brain to the muscles. This sets the stage for the primary anabolic event of the night: a massive pulse of Human Growth Hormone (HGH) from the pituitary gland. In fact, UC Berkeley research shows that growth hormone peaks during the first major deep sleep cycle, typically within the first 90-120 minutes of sleep. This HGH surge is the master signal that initiates the repair of damaged muscle fibers, strengthens bones, and mobilizes fat for energy.

Simultaneously, levels of the catabolic (breakdown) hormone cortisol are at their lowest. This creates a highly anabolic environment, maximizing the repair processes initiated by training. An athlete who trains 7 days a week is constantly in a state of elevated cortisol and sympathetic nervous system activity. This can directly suppress the ability to enter and sustain deep sleep, creating a vicious cycle: overtraining prevents the very sleep stage needed to recover from it. Prioritizing behaviors that promote deep sleep—such as a cool, dark room, avoiding alcohol and caffeine before bed, and managing stress—is therefore not a luxury, but a non-negotiable component of a serious training program.

In essence, you can train with perfect form and eat a perfect diet, but if you fail to achieve adequate deep sleep, you are denying your body the primary hormonal signal it needs to rebuild. You are leaving your growth potential on the table, locked behind a door that only deep sleep can open.

Sodium Depletion: Why Water Alone Won’t Stop Muscle Cramps?

Muscle cramps are an excruciating and common issue for hard-training athletes. The default assumption is often dehydration, leading to the reflexive advice to “drink more water.” While dehydration is a contributing factor, focusing solely on water intake is not only incomplete but can be dangerously counterproductive. The true culprit behind most exercise-associated muscle cramps is an electrolyte imbalance, specifically the depletion of sodium. Sodium is the primary extracellular electrolyte responsible for maintaining fluid balance, nerve impulse transmission, and muscle contraction. When you sweat, you lose both water and electrolytes, critically sodium.

Drinking large volumes of plain water in response to heavy sweating dilutes the remaining sodium in your bloodstream. This can lead to a condition called exercise-associated hyponatremia (low blood sodium), which is not only a cause of severe cramping but can also lead to cellular swelling, confusion, and in extreme cases, can be fatal. In fact, studies show that hyponatremia affects up to 13% of marathon runners. The muscle cramp is a loud signal from your nervous system that the electrochemical gradient required for proper muscle function has been disrupted. Water alone cannot fix this; it only exacerbates the dilution.

Effective hydration for an athlete is not about water volume, but about maintaining cellular osmosis. This means replacing not just the fluid lost, but also the electrolytes lost within it. For every pound of sweat lost during a workout, an athlete may lose anywhere from 200mg to over 700mg of sodium. A proper recovery strategy involves calculating this loss and replacing it with a beverage that contains a physiologically relevant concentration of sodium and other key electrolytes like potassium and magnesium. This ensures that the water you consume is effectively pulled into the cells where it’s needed, rather than just diluting your blood plasma.

Action Plan: Calibrating Your Electrolyte Strategy

- Monitor sweat rate: Weigh yourself without clothes before and after a one-hour training session. Each pound lost is roughly 16oz (or 500ml) of fluid.

- Calculate sodium needs: As a starting point, aim to replace 200-700mg of sodium for every pound of sweat lost. This varies greatly based on genetics and heat acclimatization.

- Time electrolyte intake: Don’t wait until you’re cramping. Begin hydrating with an electrolyte solution 2-3 hours before intense or prolonged exercise, and continue during and after.

- Balance the ecosystem: Ensure your electrolyte source includes potassium. A sodium-to-potassium ratio of approximately 2:1 to 3:1 is often effective for cellular balance.

- Recognize warning signs: Pay attention to early indicators of imbalance like muscle twitching, premature fatigue, headaches, or a feeling of being “waterlogged.” These are signals to increase electrolyte intake, not just water.

Foam Rolling: Does It Break Up Fascia or Just Cause Pain?

Foam rolling has become a ubiquitous practice in gyms worldwide, often accompanied by grimaces of pain and the belief that one is mechanically “breaking up” fascial adhesions or “knots.” This mechanical model, while intuitive, is not supported by biomechanical reality. Fascia, particularly the dense fascia lata of the IT band, is an incredibly strong connective tissue with the tensile strength of steel cable. The idea that you can produce enough force with a foam cylinder to induce a significant, lasting structural change is largely a myth.

So, if foam rolling doesn’t break up tissue, why does it often result in increased range of motion and reduced perception of soreness? The answer is not mechanical, but neurological. The benefits of foam rolling are primarily mediated through the nervous system. The intense pressure applied by the roller acts as a powerful stimulus to mechanoreceptors embedded in the muscle and fascia. This intense signal travels to the spinal cord and can temporarily inhibit or “gate” pain signals from the same area, a phenomenon known as Gate Control Theory. This provides a temporary window of reduced pain.

Research Insight: The Neurological Effect of Foam Rolling

Recent mechanistic studies have clarified the true function of foam rolling. Using advanced techniques like ultrasound imaging, researchers have demonstrated that there are no significant structural changes to the fascial tissue itself after a session of rolling. However, what they do observe are significant and immediate improvements in pain perception and joint range of motion. This indicates that the primary effect is a form of myofascial signaling. The roller provides novel sensory input that causes the central nervous system to reduce its protective muscle guarding (tonus) in the area, allowing for greater movement and a decreased sensation of tightness.

Therefore, the goal of foam rolling should not be to inflict maximum pain in an attempt to crush tissue into submission. Instead, it should be viewed as a tool to communicate with your nervous system. The approach should be slow, controlled, and focused on breathing, spending time on areas of perceived tightness to allow the nervous system to “downregulate” its protective tone. It is a tool for neurological relaxation and restoring movement, not a tool for brute-force mechanical deformation.

Active Rest: Why Lying on the Couch Is Not the Best Recovery for Stress?

After a grueling week of training, the instinct for many is to collapse on the couch for a full day of passive, motionless rest. While rest is non-negotiable, the assumption that complete inactivity is the optimal strategy for recovery is a biological misconception. For an athlete who has accumulated significant metabolic stress and muscle soreness, active recovery—low-intensity movement—is often a far superior strategy for accelerating the repair process than complete sedentary behavior.

Intense exercise produces metabolic byproducts, such as lactate and hydrogen ions, which contribute to the sensation of fatigue and muscle soreness. While the body will eventually clear these substances on its own, passive rest does little to speed up this process. Lying on the couch maintains a relatively stagnant circulatory state. In contrast, active recovery involves gentle movement that elevates the heart rate just enough to stimulate blood flow without imposing new stress on the muscular system. This enhanced circulation acts like a biological flushing system, delivering oxygen-rich blood to damaged tissues and more efficiently transporting metabolic waste products away from the muscles to be processed by the liver and kidneys.

The key is intensity. Active recovery is not another workout. It should be performed at a very low intensity, typically within a heart rate zone of 50-60% of your maximum heart rate. This level of activity is enough to promote circulation and nutrient delivery without activating the stress pathways associated with high-intensity training. Examples include a light walk, a gentle swim, a casual bike ride, or mobility exercises. This approach not only aids physical recovery but also helps in neurological downregulation, shifting the autonomic nervous system from a “fight or flight” (sympathetic) state to a “rest and digest” (parasympathetic) state, which is essential for all repair processes.

For the 7-day-a-week trainee, replacing one or two of those high-intensity sessions with a dedicated active recovery day is not a sign of weakness. It is a strategic, intelligent decision to actively facilitate the body’s cleanup and repair mechanisms, ultimately leading to better performance and reduced risk of burnout and injury.

How to Use Wearable Tech Data Without Becoming Obsessed with Numbers?

Wearable technology offers a tantalizing window into our internal biology, providing daily metrics on everything from sleep stages to Heart Rate Variability (HRV). For a data-driven athlete, this can be a powerful tool for optimizing recovery. However, it can also become a source of anxiety and maladaptive behavior, a condition sometimes referred to as “orthosomnia”—the obsession with achieving perfect sleep scores. The key to using this data effectively is to treat it as a guide, not a grade. You must shift from reacting to daily fluctuations to identifying long-term trends and using a structured system to modulate training.

Daily HRV or sleep scores can be influenced by dozens of factors, including a single glass of wine, a late meal, or even an exciting movie. Panicking and canceling a workout because of one “bad” score is often an overreaction. The real value lies in the 7-day or 14-day rolling averages. Is your baseline HRV trending downwards over two weeks? Is your resting heart rate (RHR) slowly creeping up? These are much more reliable indicators that your cumulative stress load (training + life) is exceeding your recovery capacity.

To avoid obsession and make the data actionable, implement a simple “Traffic Light” system. This provides a clear, pre-defined set of rules based on your data, removing emotional decision-making from the equation. The system works by comparing your morning’s metrics (primarily HRV and RHR) to your established baseline average:

- Green Light (Ready to Go): Your HRV is at or above your baseline, and your RHR is at or below its baseline. This indicates your nervous system is recovered and ready for stress. Proceed with your planned full-intensity training.

- Yellow Light (Proceed with Caution): Your HRV is slightly below baseline (e.g., 5-10% lower) or your RHR is slightly elevated. Your body is signaling some lingering fatigue. Do not skip training, but modulate it. Reduce overall volume or intensity by 20-30% and focus on technique.

- Red Light (Stop and Recover): Your HRV is significantly below baseline (e.g., >10% lower) and/or your RHR is significantly elevated. Your body is in a state of high stress and is not prepared to adapt positively to more training. This is a non-negotiable signal to switch to an active recovery session or take a complete rest day.

This structured approach transforms data from a source of anxiety into a productive tool for auto-regulation. It allows you to listen to your body’s objective signals and adjust your training stress accordingly, ensuring you are applying stimulus only when your body is truly ready to adapt to it.

Key Takeaways

- Muscle protein synthesis is a prolonged process, remaining elevated for at least 24 hours post-exercise, making total daily protein intake more important than immediate timing.

- Physical tissue repair peaks during NREM Stage 3 (deep sleep), driven by a surge in Human Growth Hormone (HGH) in a low-cortisol environment.

- Exercise-induced muscle cramps are primarily caused by sodium depletion, and rehydrating with plain water can worsen the electrolyte imbalance.

Mobility for Longevity: Exercises to Prevent the “Shuffle” After 60?

While muscle mass and strength are obvious goals, they are incomplete without the foundation of mobility. Longevity in movement is not just about being strong; it’s about preserving the ability to move your joints through their full, intended range of motion with control. The slow, shuffling gait often associated with aging is not an inevitability, but a symptom of a progressive loss of mobility, particularly in the hips, ankles, and thoracic spine. Preventing this decline requires a proactive, daily practice that goes beyond simple static stretching.

From a biological perspective, “use it or lose it” is the governing principle of joint health. Your joints and their surrounding tissues (ligaments, tendons, capsules) are nourished by synovial fluid, which circulates primarily through movement. When a joint’s range of motion is not regularly accessed, the tissues begin to stiffen, proprioceptive feedback to the brain diminishes, and the nervous system effectively “forgets” how to control that range. This creates a feedback loop of increasing stiffness and decreasing control, which is the precursor to the “shuffle.”

An effective mobility practice for longevity focuses on two key principles: active range of motion and motor control. Instead of passively pulling on a muscle (static stretching), the goal is to actively move a joint through its greatest pain-free range. This reinforces the neural pathways responsible for controlling that movement. Incorporating daily exercises like Controlled Articular Rotations (CARs), where you slowly and deliberately rotate a joint through its entire circumference, is a powerful way to maintain joint health and proprioception. Furthermore, focusing on fundamental movement patterns that challenge balance and coordination, such as single-leg deadlifts or deep squats, ensures that the strength you build in the gym is functional and translates to a resilient, adaptable body well into your later years.

This daily investment in mobility is the most effective insurance policy against age-related movement decline. It ensures that the robust engine you’ve built through strength training has a chassis that can handle the horsepower for decades to come, allowing you to move with freedom and confidence, not with a shuffle.

By shifting your focus from a mindset of “more is better” to a scientifically-grounded philosophy of “stress plus rest equals growth,” you can finally break through your plateau. To apply these principles effectively, the next logical step is to systematically audit your current recovery protocols and identify the critical gaps in your sleep, nutrition, and recovery routines.